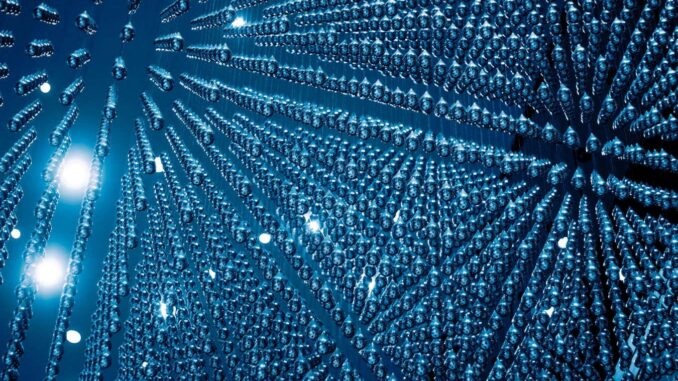

Objects are full of electrons that can interact and cause friction

Quality Stock/Alamy

Parts of the device that are perfectly smooth can still exhibit friction due to the electrons inside them, but the new method may allow the researchers to dampen it or turn it off entirely. Controlling this electronic friction could help create more efficient, long-lasting devices.

The force of friction prevents motion, dissipates energy, and exists all around us, allowing us to walk without slipping and light matches, for example. In machines like engines, friction wastes energy and causes wear, so it must be combated with lubricants and surface engineering. Still, some friction may persist regardless of these methods because the objects are full of electrons that interact with each other.

Now, Zhiping Xu at Tsinghua University in China and his colleagues devised a way to control this “electronic friction”. They made a device composed of two layers: a piece of graphite and a semiconductor made of either molybdenum and sulfur or boron and nitrogen.

All three materials are good solid lubricants, meaning that the mechanical friction caused by them sliding against each other was almost zero. This allowed the researchers to focus on a more “hidden” mechanism of wasting energy in electronic friction as the layers of the device moved, Xu says. “Even if the surfaces are perfectly sliding, the mechanical movement can still stir up the ‘sea’ of electrons in the materials,” he says.

The researchers first examined how the electronic states in the semiconductor layer corresponded to how energy was lost during sliding to confirm that they were indeed looking at electronic friction. Then they tried several methods of control.

They managed to turn it off completely by adding pressure to the device, which made the electrons between the layers share states instead of interacting in energy-expensive ways, and by adding a “bias” to the device that controlled how the electron sea could be stirred up.

Changing the voltage along two different parts of the device, which affected how easily electrons flowed through it, allowed the researchers to weaken the electronic friction — acting more like a control wheel than a switch.

Jacqueline Krim of North Carolina State University says the first studies of electronic friction date back to 1998, when her team used a material that conducts electricity perfectly at extremely low temperatures — a superconductor — to see how it disappears in this special state. Since then, researchers have been developing new ways to control it without having to completely replace materials or add new lubricants to their devices, he says.

Krim says the ideal situation would be analogous to using a smartphone app to adjust the friction of shoe soles when you’re walking from an icy sidewalk to a carpeted room, for example. “The goal is this real-time remote control with no downtime or wasted material. To achieve this, we need a material that responds to external fields in a way that provides the desired level of friction,” he says.

Xu says that managing all the types of friction present in the device is difficult in part because researchers haven’t yet developed a mathematical model that consistently links them all together. However, in cases where electronic friction is the dominant cause of wasted energy or wear, his team’s findings could already be promising, he says.

topics:

Leave a Reply