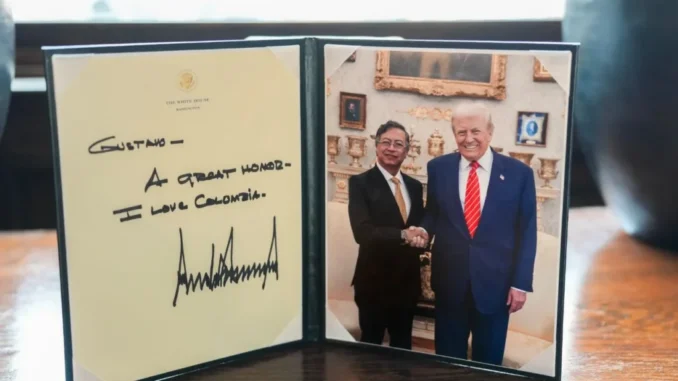

The photograph of Gustavo Petro shaking hands with Donald Trump in the White House summarizes a political turnaround which, weeks ago, seemed unlikely. The Petro-Trump meeting confirms a shift that repositions several Latin American governments in a scheme defined from Washington

Latin America in the US’s sights

After accusing the Republican of interventionism and putting democracy at risk, the Colombian president went on to appear in Washington with a calm tone and without public questions. The meeting—long, without joint statements and handled with precision by the White House— It sealed the transition from the confrontation to a framework marked by the United States.

You may also be interested in: Agreement contains another government shutdown in Washington

This turn has a clear trigger. For political scientist José Luis Valdés Ugalde, the capture, just a month ago, of Nicolás Maduro was “a watershed” that inaugurated a “Trump Corollary based on Monroe Doctrine”, a model that imposes conditions “by force and imposition.”

The fall of hardline Chavismo—the most openly anti-American actor on the continent—left several governments without a symbolic axis of resistance. With this void, a pragmatic rearrangement emerged: Brazil qualified his speech, Mexico negotiate to avoid friction, the Caribbean check your energy balance and Colombia It repositions itself quickly. Washington, the academic summarizes, “imposed terms in which Latin America will live under pressure.”

Change of speech

The realignment occurs in a hemisphere that was already tilted to the right. Conservative and center-right advances in Paraguay, Ecuador, Panama, Uruguay, El Salvador, Argentina, Peru or Costa Rica They have reduced the ideological counterweight that previously limited American influence.

In this new operational order, the head of the White House has outlined a method: punishment, pressure and reward. The exemplary punishment was Maduro; pressure is expressed through tariff threats; The rewards—economic flexibilities and conditional openings—function as incentives to align.

In that sense, the Colombian read the script. The extradition of a drug lord to Washington, announced hours before the meeting, opened space to de-escalate tensions, accompanied by a narrative of crop substitution and the symbolic gifts—coffee and chocolates—given by the president. “Petro is paying for mistakes, but he is also aligning himself so that Trump does not punish him the same as Maduro,” says Valdés Ugalde.

Mexico with ‘gun to the temple’

The capture of Hugo Chávez’s successor made it clear that the Trump administration is willing to employ judicial, financial and military instruments to discipline his adversaries. “Mexico has the gun to its head,” warns Valdés Ugalde when referring to the pressure on the oil sent to Cuba and the risk of “surgical” operations linked to the fight against drug trafficking.

For Havana, the message points to the brink of economic collapse if it does not agree to negotiate. For the rest of the continent, the conclusion is unequivocal: the margin to challenge Washington narrowed abruptly.

Beyond ideological narratives, the region is entering a phase of constant calibration: governments that could previously afford gestures of distance now adjust each movement to avoid sanctions or retaliation. Petro’s photo is symptom and synthesis from that moment.

Behind—as Valdés Ugalde points out—emerges “a hemisphere where Washington once again sets the pace” and where prudence becomes a political survival strategy.

Leave a Reply