When the Court of Arbitration for Sport decision came down, Jobe Watson wasn’t thinking about his Brownlow Medal. Others were. It’s been an important conversation in AFL scenario planning and a question long pondered at Essendon.

With the decision wiping out the 2016 season for active players among Essendon’s 34 – a dozen of them still on the Bombers’ list at the time – it was understandable that the captain was more concerned with his then-teammates and former players.

In the immediate aftermath of one of the most significant days in Australian sport, the individual impact was trumped by the team impact.

“The Brownlow was probably more of a question as the year went on where it started to become more front and center for me, I think, realizing what it might look like and what the consequences would be. But it wasn’t something I thought about immediately,” Watson said.

“It was like a wound that festered, you know. You get to a point where you accept you can’t play for 12 months and that’s the reality of your situation. So you can hang on and you can move on.

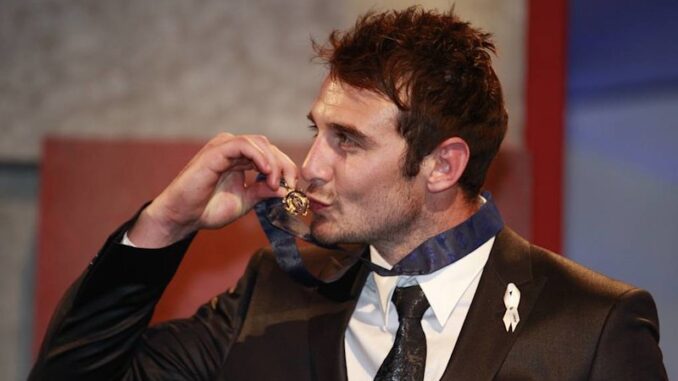

Watson on Brownlow night in 2012. Credit: Paul Rover

“But Brownlow was part of it, that was the wound that wouldn’t heal, that was still infected, and as the year went on it got more and more infected. That’s the way it was.”

“It was something that was still there and no one had any clear idea of what it was going to look like and it wasn’t communicated to me until the end of the year, really, so it felt like something to celebrate.”

A Brownlow medal, the captain’s chair at Essendon and the Watson surname meant Jobe bore much of the focus of the suspension.

Forcing Brownlow to pay back for a doping offense was, in a way, additional punishment.

Watson during his time in New York.Credit: Domain

Ten years on from the day 34 players were suspended – January 12, 2016 – Watson is now at peace with what happened. Since his retirement in 2017 he has lived and run a cafe in New York where he met his wife Virginia and is now Managing Director of Watson Property Advisors in Melbourne. He remained associated with football as a special commentator on Channel Seven.

But with three elementary school-aged children, he admits he wondered how he would discuss what happened when they were old enough to understand.

“It’s an interesting question and something I’ve thought about at times. At the moment I don’t think they actually believe I played,” he said.

“But I think I’ll just explain to them that sometimes things are out of your control and all you can do is deal with the scenario you’re faced with. I’ll say I don’t believe I did anything wrong, I don’t believe I cheated the system, but other people found out that we did. I don’t think that’s an unreasonable position.

“You can believe you didn’t do anything wrong when someone else finds out you did. But you can dwell on it and it can be the story of your life, or you can move on from it.”

“There’s going to be times, and I think I’ll tell my kids, when people do things to you that you think are unfair or that you don’t think are right, and you can carry that for the rest of your life and have that be the way you approach everything in life, and it’s going to determine how you live the rest of your life, or you can accept it and move on.”

“It takes time, but time heals everything, you know.

Watson with his daughter and the horse he co-owns, Annavisto, at Flemington in 2023. Tom Bellchambers and Cale Hooker are also part owners.Credit: Getty Images

Five years ago, Watson said, the Brownlow conversation would have been raw.

“It was deeply painful to have to give Brownlow back,” Watson said. “But you know, it’s life – you can move on from it. It was just an appreciation.”

“I’m often asked, ‘How do you feel about it?’ And I’m like, ‘Look, I have incredible memories of winning the Brownlow Medal’. Got to celebrate with mom and dad at an event. After that I had all my family and friends come and celebrate with me. I had a week of celebrations with all my friends. It is still talked about today. And for me, the whole experience of winning a medal is a joy and recognition of the effort and work put in. There are parts of it now that were painful afterwards, but I still look back on the experience.’

Another regular question is why the players didn’t call the sports science team when they were getting stomach injections in the sports scientist’s office.

In the eyes of the players, there was no reason to fight back. They trusted the club leaders from the coach and football manager to the club doctor knew that the players were getting injections and were assured that nothing was wrong.

As then-chief executive Ian Robson said when announcing his announcement: “We let our players and their families down… There is no excuse for not knowing [what happened] and as CEO I am responsible.”

CAS found this explanation understandable but unsatisfactory, given that none of the players had reported thymosin injections on declaration forms during drug testing.

Watson’s current attitude to the whole process is different than it was. For a long time it was too raw to discuss in detail. He is now more phlegmatic, not wanting it to define the rest of his life as it marked his playing career.

“I look back on it now and there’s still disappointment and frustration with the whole scenario and what it did to the players’ careers, what it did to my career, what it did to the environment that we created. And I think that’s something that’s just part of the experience. It’s not something I dwell on,” he said.

“The frustration of what could have happened when we were at the club and then the consequences of that and the way those consequences played out and the length of those consequences and what it meant to players’ careers and how long it took for that to happen.”

“I guess I’m still clinging to the evidence. I don’t think I’m ignorant or naive to the evidence because I’ve absorbed it all and I’ve been involved to some extent by giving evidence, but also by actively reading and gathering evidence through transcripts. So I think there’s still a degree of frustration with what was presented and then the implications of that evidence and the verdict that was found.”

“I think the consequences, and it’s true in life, in all aspects of life, is that whatever happens to you, it’s felt more by the people around you than you. And that’s with everything – illness, tragedy, anything like that. And it’s the same for us and it’s the same for my parents. It’s the same for family members. It’s the same for family members of all the other players.”

“She was an anchor for the club”

The impact of the doping saga was profound. He split groups within the club. His impact on players and performance on the pitch was significant. It’s not the only reason Essendon has been poor on the field over the past decade, but it has had a lasting impact.

“I think he’s been an anchor for the club ever since,” Watson said.

“And not just financial. The team we put together at the time looked like a very strong side, a very talented side and players left as a direct result of what happened. And we lost good players but we also lost momentum and we lost the ability to improve and play together for 12 months and then we have to come back and try again.”

But, as Watson explained, it wasn’t just the suspension season that affected it.

“Also, the 2012 season was difficult because you’re dealing with real people and their erratic behavior. The 2013 season was affected by what happened with the investigation. Season 14 is affected because you lose one coach and another coach comes in. Season 15 is affected because you got a hearing, [and] then you have an appeal. And then season 16 is affected because you’re out, and then season 17 because you missed 12 months.

“So it’s not just that you’ve missed 12 months and it’s been fine. That’s the frustration and the thing you’re probably angriest about as a player is that it’s affected a five-year period of your career.”

“There are guys who are your teammates who came to the club in 2012, who left in 2015 or 16, and their whole experience has been such chaos and what they think football has been, or that’s been their reality… And that’s really sad for guys who were trying to live their dream and it wasn’t their own fault. Their whole experience was in the AFL system.”

“So I think the anchor that I’m talking about was that the club and the playing group was ready and it was a five-year layoff and then that caused the profile of the roster to change drastically.

Then-Essendon president Lindsay Tanner on the day the players were suspended.Credit: Getty Images

Former Essendon president Lindsay Tanner agrees and also notes the impact of lost draft picks from the AFL penalty. These are players who, if the Bombers had drafted correctly, would now be in their prime playing years.

“I think you’d have to say the impact of the whole issue on the results on the pitch was significant, but there are bigger factors at play, like at the end of the day as a club we make decisions about recruiting players, drafting players, signing coaches, assistant coaches,” Tanner said.

“I wouldn’t want to throw it all away. [to the CAS decision]. But it’s certainly not irrelevant.

“I have said to the members numerous times that yes, there are aspects of this whole saga that I think have been completely outrageous and unfair, but never forget that if we had run the club properly none of this would have happened.

“So the consequences we experience, while painful, [are] all the consequences we have effectively brought upon ourselves.’

Read the first part of this two-part series here.

Stay up to date with the best AFL coverage in the country. Sign up for the Real Footy newsletter.

Leave a Reply