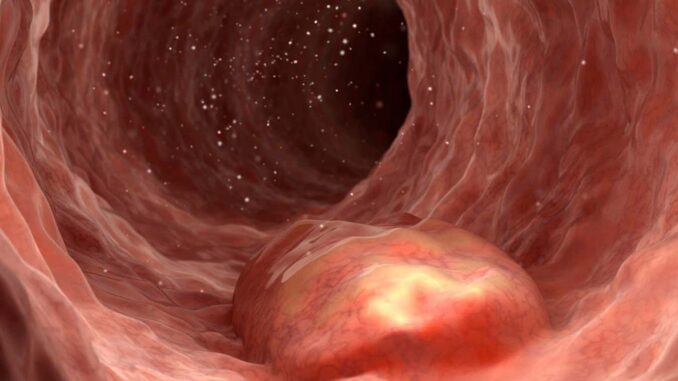

Inflammatory bowel disease can cause bleeding wounds

SPRINGER MEDICINE/SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY

Scientists looking to provide relief to people with inflammatory bowel disease have turned to an unusual source of inspiration: the villous plant.

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), such as Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis, appears to occur when someone’s immune system attacks the gut, leaving it inflamed. Its main symptoms are diarrhea, severe abdominal pain, weight loss and bleeding from the intestine into the stool.

Anti-inflammatory drugs such as steroids can relieve symptoms. However, if the bleeding persists, doctors may use small metal staples that are inserted into the intestine through the anus to close wounds caused by inflammation. However, this carries the risk of infection and can even make the wounds worse.

In search of a more subtle approach, scientists previously genetically engineered bacteria to produce substances that help heal wounds. However, these microbes are usually cleared from the gut within a few days and it must be activated manually with drugshe says Bolin An at the Shenzhen Institute of Synthetic Biology in China.

Now, An and his colleagues have genetically engineered a harmless strain Escherichia coli bacteria to produce a protein fragment that promotes wound healing after blood sampling. Crucially, the bacteria also make certain types of “cement proteins” that the worms use to attach themselves to underwater surfaces. Based on tests in lab dishes, the team hoped these proteins would act as an anti-inflammatory seal against bleeding wounds, calling it “living glue.”

To test this, the researchers used a toxic chemical to induce IBD-like problems—including inflammation and intestinal injury that led to weight loss—in mice. Each mouse then received either a single dose of the innocuous unmodified strain E.coligenetically modified E.coli or saline, all of which were delivered to the gut via a tube through the anus.

Ten days later, the mice that received the engineered bacteria, which were still present in their guts, regained most of the weight they had lost. Unlike the other two groups, their insides even resembled healthy mice. None of the mice showed signs of side effects.

The team also saw similar effects when mice were given a pill containing the bacteria, suggesting the approach could one day be administered orally to humans. “It’s definitely promising, and it’s a new approach,” he says Shaji Sebastian at Hull University in Great Britain. Healing of intestinal wounds and inflammation in mice is quite similar to that in humans, although human tests are needed, he says.

The researchers now plan to test the approach in larger animals, including pigs, in part to determine how long the engineered bacteria can be retained in the gut, An says. But it could take up to 10 years to reach clinics because so much testing is needed to show that it not only works but also offers advantages over existing treatments in humans, Sebastian says.

topics:

Leave a Reply