There are court decisions that don’t just fix a bad law if they shed some light on the context from which the word is being used to misrepresent. The declaration of the unconstitutionality of the crime of “cyberasedio” in Puebla is one of them.

After July passed, this criminal character is now on the list to be used. A vaguely worded crime capable of turning inconvenient criticism, public complaint or discussion in social circles into a criminal matter. Enough for someone to feel “hosted” or “hurt” by an opinion or any expression in social circles to open the door to criminalization.

A judge who approved the provisions enforced by Article 19, with strong legal support from PROJUC, is much needed. I have heard that other district (federal) judges have been promoted by civil organizations for the proposal and the National Council on Extraordinary Litigation. Basically, I’m saying that criminal law cannot be a path to regular expression, much less in digital environments where public conversation is intense, pluralistic, and by definition inconvenient for power. Penalizing speech does not prevent violence creates an inhibitory effect on public debate before a prison sentence.

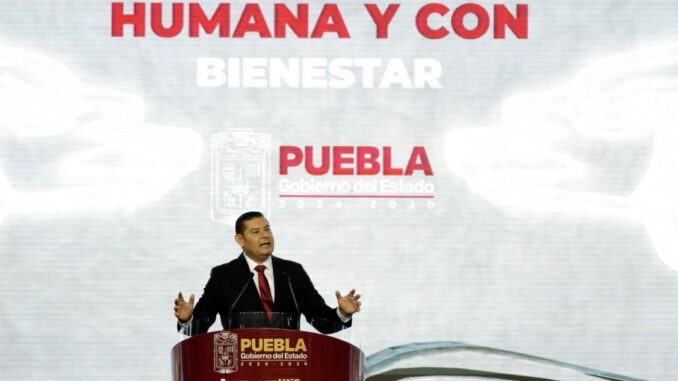

This foul carries particular weight in Puebla, a state in which the current government has shown little tolerance for criticism and social control. Governor Alejandro Armenta’s style – with public whitewash, confrontation, legal persecution and a discourse that makes enemies where there are questions – clearly shows the risk that implies a norm like “cybersedio”. In this context, it was clear that the public government wants to brake, stop, stop. Therefore, as explained in Article 19 in its form “Laws as a Censorship Mechanism: Increasing Judicial Enforcement Against Journalists in Mexico”Puebla is part of a group of six states with the most cases of judicial harassment against the outlet.

But there is more that should not be overlooked. This battery connects just when you’re running low on juice. Reforms introduced last year to limit legitimate interests, reduce the effects of suspensions and thereby close the door to human rights lawsuits are likely to weaken one of the few actions that still allow citizens to defend themselves against abuses of power.

The Pueblo case shows why this matters. Unless journalists (individually or collectively) and organizations challenge the rule that applies to everyone, censorship has become normalized with little semblance of legality.

It also confirms that without independent wills, with a reserve to limit excesses, the blade was extinguished on its own. We won’t ask you to ring again, but we have more hope. Local jurisdictions are linked to political interests that appeal to journalists and are evident (see Puebla, Campeche or Veracruz). Even now that judicial reform has made an even more desperate grasp of the same things.

Now, however, the (new) judiciary of the Federación has reached an acceptable balance in the matter of freedom of expression. Including the SCJN this week declared “halconeo” an unconstitutional crime in Sinaloa to block coverage of violence committed by Sinaloa cartel faces.

Another lesson is that ongoing social articulation is essential. Without organized journalists, active citizens, organizations with the ability to litigate, and critical public voices, these kinds of restrictions on free speech have gone unchallenged. The terrain developed in the legal dispute led to a conflict between permissive officialism and censorship when it was not overtly proactive in imposing it.

In this story, even if it ends, there will definitely be another chapter. The Congreso de Puebla can and will be a challenge. It would be very unfortunate if the court or including the SCJN overturned this important decision and similar resolutions dictated in favor of other journalists and organizations. But in a highly politicized judiciary, anything can happen. We hope that law and justice will prevail and that no matter what this case is, we will move forward with censorship in Mexico.

Leave a Reply