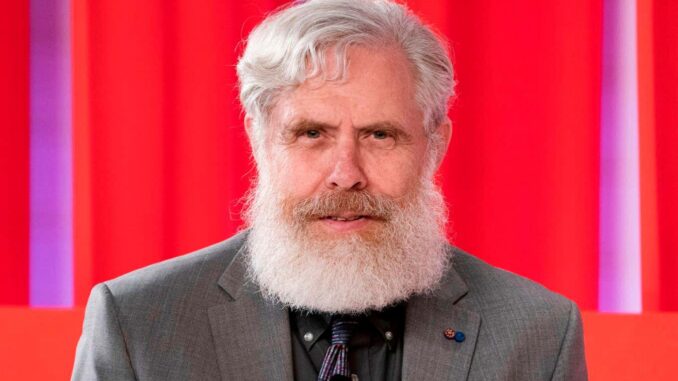

Biologist George Church maintains a list of potentially beneficial gene variants

DON EMMERT/AFP via Getty Images

“Why should only the tall have access to tall genes? And why should only the smart have access to smart genes?… our goal is to give as many people as possible the opportunity to choose their genes for themselves (and their offspring) rather than simply accepting inherited genetic inequality. Because genetics should not be a lottery.”

That’s the playground Bootstrap Bioa start-up openly aimed at one day offering potential parents the chance to genetically enhance their children. I would say that the children of anyone who could afford such a service have already won the lottery of life, but the more immediate question is: could we really genetically enhance our children if we wanted to?

To understand what might be possible, I started with list of “protective and enhancing” gene variants led by biologist George Church of Harvard University. When I asked Church what the purpose of the list was, he told me that he started it in response to questions that came up during lectures, from whether all rare gene variants are harmful to what kinds of genetic enhancements might be possible. The list is popular with transhumanists who want to use genetic engineering to create superhumans.

So let’s see what’s on it.

Would you really like extra fingers?

The list is rather mixed. It now contains more than 100 entries, but only about half are specific gene mutations or variants that have been identified in humans and associated with specific effects (the rest relate to animal studies or medical tests). Church singled out mutations that could have an unusually large “positive effect,” from protection against certain diseases to a reduction in male aggression.

For me, some of the features on the list are anything but desirable. For example, he states that unspecified changes in a single gene could improve a person’s “manipulative ability” by giving them six fingers on each hand. Really? Would you want six fingers even if you did? Imagine trying to buy gloves!

Also shown are two gene deletions that result in insensitivity to pain. But that’s not an improvement: children who don’t feel pain are known to end up with terrible injuries.

Most of the other traits on the list fall into the “nice to have but not worth resorting to genetic engineering” category for me. Take “low odor production” – that doesn’t seem essential in the age of deodorants. Sure, I’d like to be able to hold my breath longer or handle high altitude better, but I’m not sure any of my offspring would care.

Only a few of the variants on the list were associated with generally appealing traits, such as longer life or higher intelligence—something that wealthy potential parents could pay extra for. But we are still very far from the point where we can be sure that introducing these variants into children would actually make them smarter or live longer. We simply don’t know enough.

Designed to sleep less – but at what cost?

For starters, it may turn out that some of these associations are wrong, that some of the gene variants don’t have the effects we think. Or they might have the desired effect only in conjunction with certain other genetic variants.

Moreover, there are often compromises. For example, one variant associated with higher intelligence may increase the risk of blindness later in life, according to Church’s list, while resistance to norovirus may increase the risk of Crohn’s disease. I think I’d rather be a little dumber and put up with the occasional bout of norovirus. You might feel differently—and your future children might end up thanking or healing any such decision you make for their benefit.

There are no disadvantages noted for most variants on the list, but that doesn’t mean there aren’t any. Take, for example, variants associated with less sleep. Given the critical importance of sleep to brain health, it seems very likely to me that there are some trade-offs.

I don’t think many people realize that our understanding of genetic variants like these is not only in its infancy, but in many cases we may never be able to be sure whether a particular change will be beneficial. That’s because to determine the good and bad effects of a genetic variant, biologists need to look at tens of thousands of people who have it, or even more.

How can we really make life’s lottery fairer

This means that to maximize the likelihood that any individual would actually benefit from genetic engineering, you would have to make dozens or hundreds of changes at once. This is especially true for the traits mentioned by Bootstrap Bio, since height and intelligence are determined by hundreds of variants, each of which has a small effect. The catch is that we don’t yet have the ability to safely make a few changes to human embryos, let alone hundreds at once, as I described in my previous column on preventing hereditary diseases.

I’m not saying all this because I’m against genetically enhancing our children. On the contrary, I’m actually in favor of it – it’s better than letting children’s destinies be determined by random rolls of the genetic dice. But I am very far from convinced that we should try to edit the hereditary genome anytime soon. And we don’t need startups like Bootstrap Bio to get to the point where we can seriously consider it. Instead, we need to massively scale up studies like the UK Biobank, which follow large numbers of people over several decades, to get much clearer ideas about the pros and cons of genetic variants like those on Church’s list.

As for the idea that companies selling genetic enhancements will make the world fairer, pull the latter. ON a fifth of children Births around the world today end up shorter than they should be and with impaired cognitive abilities because they are not getting the right nutrition. Even more people are not getting a good education. Anyone seriously interested in how to lottery a child’s life chances might want to focus on ensuring that those millions of children can reach their existing genetic potential rather than trying to boost the genes of a few.

topics:

Leave a Reply