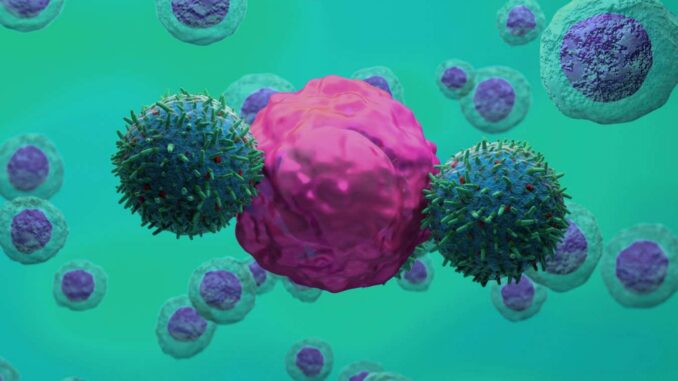

Illustration of CAR T-cell therapy (green) attacking a cancer cell (pink)

NEMES LASZLO/SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY

Genetically engineered immune cells known as CAR-T cells may be able to slow the progression of the neurodegenerative condition amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) by killing rogue immune cells in the brain.

“It’s not a way to cure a disease,” he says David Trotti at the Jefferson Weinberg ALS Center in Pennsylvania. “The goal is to slow down the disease.”

Life expectancy for people diagnosed with ALS is only two to five years, so slowing the progression of the disease would make a big difference, Trotti says. It’s possible that the same approach could help slow down other neurodegenerative conditions as well.

ALS, also known as Lou Gehrig’s disease, is caused by the loss of motor neurons, the nerve cells that control voluntary muscles. Physicist Stephen Hawking had ALS, but his case was exceptional because he lived so long. Less than 10 percent of people diagnosed with the disease survive more than ten years.

There has been some progress in developing treatments for forms of ALS caused by genetic mutations, Trotti says, but these account for only 5 to 10 percent of cases. There is no treatment for sporadic forms of ALS, the causes of which are unknown.

However, there is evidence that inflammation in the brain contributes to death of motor neurons. In particular, certain immune cells known as microglia appear to go into a hyperactive state.

Microglia usually protect the brain from infections, cleaning up any debris and helping to prune excess connections, or synapses, between neurons. However, if some of them become overactive, they can remove too many synapses and contribute to neuron loss. “They get out of hand,” says Trotti.

In a series of experiments that involved studying brain and spinal cord tissue from people with ALS, Trotti’s team showed that these damage-amplifying microglia, as they’re known, have a protein called uPAR protruding from their surface. “So they’re tagged, and when we know the tag, we can go after them and remove them from the central nervous system,” says Trotti.

To do this, his team turned to CAR-T cells, immune cells genetically engineered to kill cells with specific proteins on their surface. CAR-T cells have proven very effective in treating certain types of cancer and are now being tested for treating a much wider range of diseases, such as autoimmune lupus.

In studies of cells growing in culture, the team showed that uPAR-targeted CAR-T cells could kill rogue microglia without damaging neurons. So while this treatment can’t replace lost motor neurons, we hope it will significantly slow further loss.

Trials are now underway on mice with a mutation that causes them to develop a form of ALS, with results expected within a year. The severity of ALS and lack of treatment means that regulators may help speed up human trials if those results are promising.

“The evidence for immune dysfunction in ALS is mounting,” he says Ammar Al-Chalabi at King’s College London, whose team has tested immune therapies for ALS. “This seems like a very promising and interesting approach to me.”

It is likely that damage-amplifying microglia also contribute to other neurodegenerative conditions, possibly including types of dementia, so this treatment may prove to have broader applications beyond ALS. “This could be a way to slow down these kinds of neurodegenerative conditions,” says Trotti.

CAR-T cells have some major drawbacks as a therapy: they can cause serious side effects, and because they are usually derived from a person’s own cells, they are very expensive to produce. But many teams around the world are working on ways to make them safer and cheaper, such as by generating them in the body so the cells don’t have to be extracted.

Leave a Reply