The keys

nuevo

Generated with AI

nuevo

Generated with AI

Japan will hold early general elections this Sunday in a call that comes just over a year after the last elections and just three months after the coming to power of Sanae Takaichi. This is an unusual schedule even for a system accustomed to political volatility.

The advance responds to a clearly political decision and reveals the new prime minister’s willingness to submit to the polls a project that has not yet been electorally validated and that points to a break with some of the consensuses that have defined Japanese politics in recent decades.

The electoral advance is largely due to a strategic calculation by the Liberal Democratic Party (PLD), in power almost uninterruptedly since 1955.

Takaichi seeks to take advantage of a window of opportunity before the wear and tear of the Government, the internal tensions within the PLD itself or the social and diplomatic consequences of his first decisions begin to become visible.

The appointment with the polls thus becomes a tool to consolidate its leadership and reinforce its authority in a system traditionally marked by the balance between factions of the same party.

Faced with the advance of the ruling party, the opposition arrives at the polls deeply fragmented, a weakness that, by contrast, reinforces the story of inevitability projected by the Government.

The creation of the Chūdō Kaikaku Rengō, a forced alliance between the Constitutional Democratic Party (PDC) and the Kōmeitō after the latter’s break with the LDP, has been received with skepticism by both analysts and the bases themselves.

The new bloc was born without a clear common narrative and with difficulties in mobilizing an electorate accustomed for decades to cooperation between the LDP and the Kōmeitō.

The legacy of that long collaboration weighs especially heavily in this campaign.

For years, both parties built territorial networks, local loyalties and electoral mobilization mechanisms that today are difficult to reconvert in favor of an improvised opposition.

Rather than a coherent government alternative, the new alliance appears as a tactical sum designed to minimize damage, which limits its ability to contest political leadership to Takaichi and reduces the contest to an implicit validation of the Executive’s project.

Beyond the electoral calculation, the call comes at a time of redefinition of the country’s political course, marked by a hardening of the discourse on security and national identity.

In just a few weeks, the Government has promoted a more restrictive line regarding immigrationhas reopened debates until now considered taboo – such as the possibility of providing Japan with its own nuclear capabilities in an increasingly unstable regional environment – and has raised the tone in its relationship with China, recovered as a central threat in the official narrative.

This shift not only has internal implications, but places Japan in a new position within the strategic balance of East Asia and tests the limits of the constitutional pacifism that has defined the country since the postwar period.

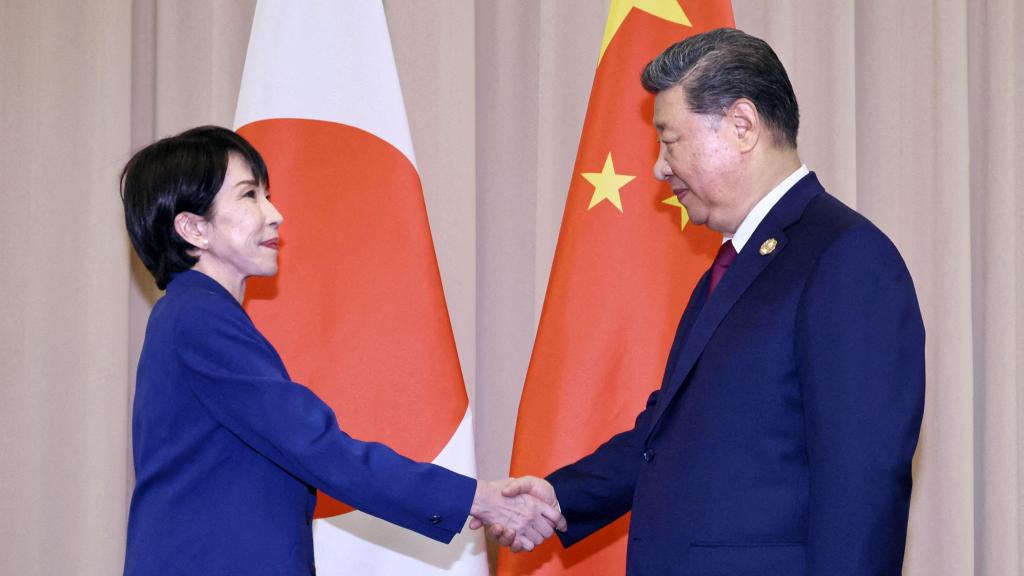

Japanese Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi shakes hands with Chinese President Xi Jinping before their talks in Gyeongju, South Korea.

In parallel to this ideological turn, the Executive has deployed a package of measures of a marked electoral nature aimed at alleviating, in the short term, the social unrest caused by inflation and wage stagnation.

Among the most visible initiatives are the temporary reduction in the price of gasoline (reaching less than 138 yen, about 0.70 euros per liter), the drastic reduction in passport costs and other administrative procedures for Japanese citizens, as well as the reopening of the debate on a possible reduction in consumption VAT, currently set at 10%.

Populist and easily communicable measures, with an immediate impact on the perception of families, but which avoid addressing the structural imbalances of the Japanese economy, such as the precariousness of employment, the loss of purchasing power or the long-term sustainability of the economy. welfare state in an increasingly aging society.

One of the central axes of the campaign is the tightening of immigration policy, articulated through a set of measures aimed at limiting the arrival and stay of foreigners in a country that, paradoxically, increasingly depends on foreign labor.

The Government has announced a reinforcement of visa controls, a greater capacity for expulsion for people with irregular or expired permits and a downward review of certain temporary work programs.

It has also emphasized stricter control of access to social services, arguing to protect public resources for Japanese citizens.

These decisions collide with the demographic reality of the country, marked by a sustained decline in the active population and key sectors – such as construction, long-term care or agriculture – that already suffer from a chronic shortage of workers.

Beyond the concrete measures, what is most significant is the tone of the government’s discourse, which has abandoned the traditional Japanese ambiguity on immigration to adopt a clearly identity-based narrative.

Without resorting to openly xenophobic rhetoric, Takaichi has insisted on the need to preserve the country’s “social cohesion”, “public order” and “cultural values”, concepts that function as an implicit framework of distrust towards foreigners.

A language until recently marginal in institutional discourse, which connects with the most conservative sectors of the electorate and reflects a global tendency to instrumentalize immigration as a political problem.

The risk, several analysts warn, is that Japan ends up turning a structural need into an identity conflict that is difficult to manage.

Another of the most delicate elements introduced in this campaign is the reappearance of the debate on nuclear weapons, one of the big taboos of postwar Japanese politics.

Without formulating explicit proposals or formal commitments, key figures around Takaichi have begun to publicly legitimize the discussion on the desirability of equipping itself with capabilities. nuclear own, in response to the deterioration of the regional security environment.

The simple displacement of this issue from the realm of the unthinkable to the realm of the debatable represents a profound break with the consensus built after Hiroshima and Nagasaki and opens the door to a redefinition of the moral and political limits of the Japanese State, beyond the immediate result of the elections.

In parallel, the relationship with China has been explicitly incorporated into the electoral narrative as the main focus of external tension.

The Government has recovered a discourse that places Beijing as the greatest strategic threat to Japan, both militarily and technologically, reinforcing a narrative of permanent pressure that legitimizes the hardening of defense policy and the search for electoral support in the key of national firmness.

China reappears as well as structural enemy in the official discourse, an effective resource to unite the conservative electorate and move the political debate towards the terrain of security and identity.

This approach, however, simplifies a much more complex relationship.

China remains the main business partner of Japan and a central player in its industrial and technological supply chains.

The instrumentalization of foreign policy for electoral purposes ignores this interdependence and runs the risk of translating into economic, diplomatic and strategic costs in the short and medium term.

By making the rivalry with Beijing a central axis of the campaign, the Executive introduces a structural tension factor that transcends the electoral cycle and conditions the country’s room for maneuver in a regional environment already marked by instability.

Beyond the calendar and the electoral result, the early call reveals an underlying political strategy: using the ballot box as a mechanism for accelerated validation of an ideological turn before it encounters more structured social and institutional resistance.

In this context, the Takaichi Executive has opted for a formula known in other political scenarios: the identification of an internal enemy, associated with immigration, and an external enemy, embodied in China, as tools to gather support and move the public debate towards the terrain of identity and security.

The result is a combination of short-range economic measures, an increasingly explicit identity discourse and the questioning of historical consensus that threatens to permanently alter the balance of the Japanese political system and the limits of the democratic consensus built in the post-war period.

Leave a Reply