There is a feeling that is becoming more and more widespread, and not only among people “living” in the digital world: many things that used to work well now work worse. Not because the technology became more difficult, nor because the technical possibilities were lacking until someone in some growing committee decided it was viable and would work better.

It’s a deliberate, calculated and sensible degradation: less control for the user, more friction, more notifications, more ability to type, more “surprises” of features that disappear, if you care or have it invoiced separately.

And what’s interesting is not the momentary impact, but the cumulative effect: if it destroys trust as an economic asset, and that has consequences for people, companies and the competing team.

The logic is quite simple. When a digital product gains critical mass, the incentive starts to “improve” and becomes “extraer más”. In a market with salty fricciones, with red effects and with the psychological cost of migration, the tester can afford small claims without paying the immediate price.

The trick is in the dosage: a little more publicity here, a little more price there, functionality that used to be standard and is now converted to “insurance premium”an interface that prompts you to accept what is not right for you. Each change, in particular, seems to be tolerable. Moreover, it is a strategy that Cory masterfully executed “concern”when things happen, gradually and on purpose, to make a mistake.

Defiance, once installed, is non-negotiable: it infects

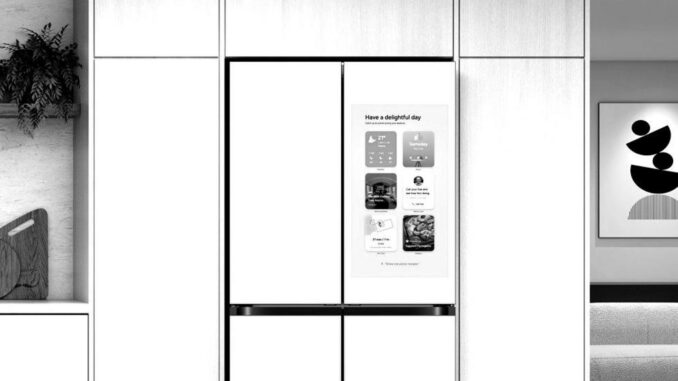

We see it in the devices and services we have normalized as part of the household. Connected TV platforms are testing notifications more and more intrusively, until now the point is to experiment with formats that interrupt the light or colonize the main panel.

The user reaction is usually visceral, but the company plays a different game: I wonder which percentage protests, which percentage resists, and which percentage eventually buy a “solution” (e.g. pay for less ads or switch devices within the same ecosystem). It is laboratory economics applied to millions of people.

We see it even in “serious” products, from those that support enterprising companies. Forced conversion of perpetual licenses to subscriptions, mandatory bundling of features that aren’t needed, or radical price increases with “higher value” restrictions are moves that can improve short-term inputs, but be aware: CIOs and purchasing managers who commit are treating your claimants as powerful adversaries, not partners.

And when that relationship breaks down, it accelerates something that tech companies tend to underestimate: the desire to escape, to diversify, to seek alternatives, however imperfect. Defiance, once installed, is non-negotiable: it infects.

Another variant, the most corrosive, is redeño degradation: “updates” that hold the promise of modernity and eliminate essential functionality, accessibility, or behavior that the user has adopted. This is not a technical error, this is a product decision: shorten, simplify the business, reorder for money, fill in the next step of the mix.

Deliberate degradation creates a “priority of suspicion” that applies to the entire sector

A typical case is that a person finds that the appliance they bought is the same, but the experience has improved because of it softwarewhich used to respect one logic, now responds to another: growth.

And here are the dark patrons, this professional discipline of designing the interface so that the user has what he would not fully understand the decision. Subscribe in two clicks, cancel in six pages; accept everything with a large button, replace with a gray tie; prices presented in such a way that the most expensive option appears “reasonable”.

Let’s not talk about intuition: there are international teachers and regulatory analyzes that take time to notice the extent of this phenomenon. What’s so common isn’t anecdotal, it’s structural: if so many companies do it, it’s because it works, and if it works, it’s because the real cost of reputation is less than you deserve.

A key point emerges here: the harm is not only moral, it is economic. Deliberate degradation creates a “priority of suspicion” that applies to the entire sector. Either the company will convert what was standard to extra or make it harder to cancel, encouraging the consumer to avoid the next company.

Even after a platform decides its launcher is ad-supported, it makes the user suspicious of the next device they buy. The result is a more cynical society in relation to digital and businesses that are paradoxically more successful in marketing, v “reputation” and artificial containment to compensate for what they destroyed.

This is not a question for domestic consumption. Loss of trust changes behavior: more people look for versions “argument”blockers, alternative systems, early purchases instead of subscriptions, hardware menos “intelligent”, or simply renunciation.

Use crisis plans and strategies in companies multivendorturn to the solution open source or heavier contracts. Socially, it widens the gap: those with time, acquaintances or resources are better protected; nobody, pay more and suffer more friction. It is a silent form of digital design.

what to do The answer is not romantic: no more “choose better” because real choices are usually limited by monopolies de factocompatibilities, dependencies, and salt costs. The most effective platform is to reduce these fricciones: portability, interoperability, ease of cancellation, effective prohibition of obscure readers and real competence. If the climbing is easy, a deliberate degradation pays off. If climbing is difficult, if it is rewarding.

However, it is worth reiterating a simple idea here: when the company tells you “this is for your experience” I was saying “this is for our money”.

And as common as the products are for this purpose, the more expensive it is to rebuild what is lost: trust as the invisible infrastructure of the digital economy.

***Enrique Dans is Professor of Innovation at IE University.

Leave a Reply